☰

Zaab Zaab

“The restaurant business isn’t for anyone who doesn’t have passion,”

said Bangkok-born Bryan Chunton, co-owner of Northeastern Thai restaurant Zaab Zaab.

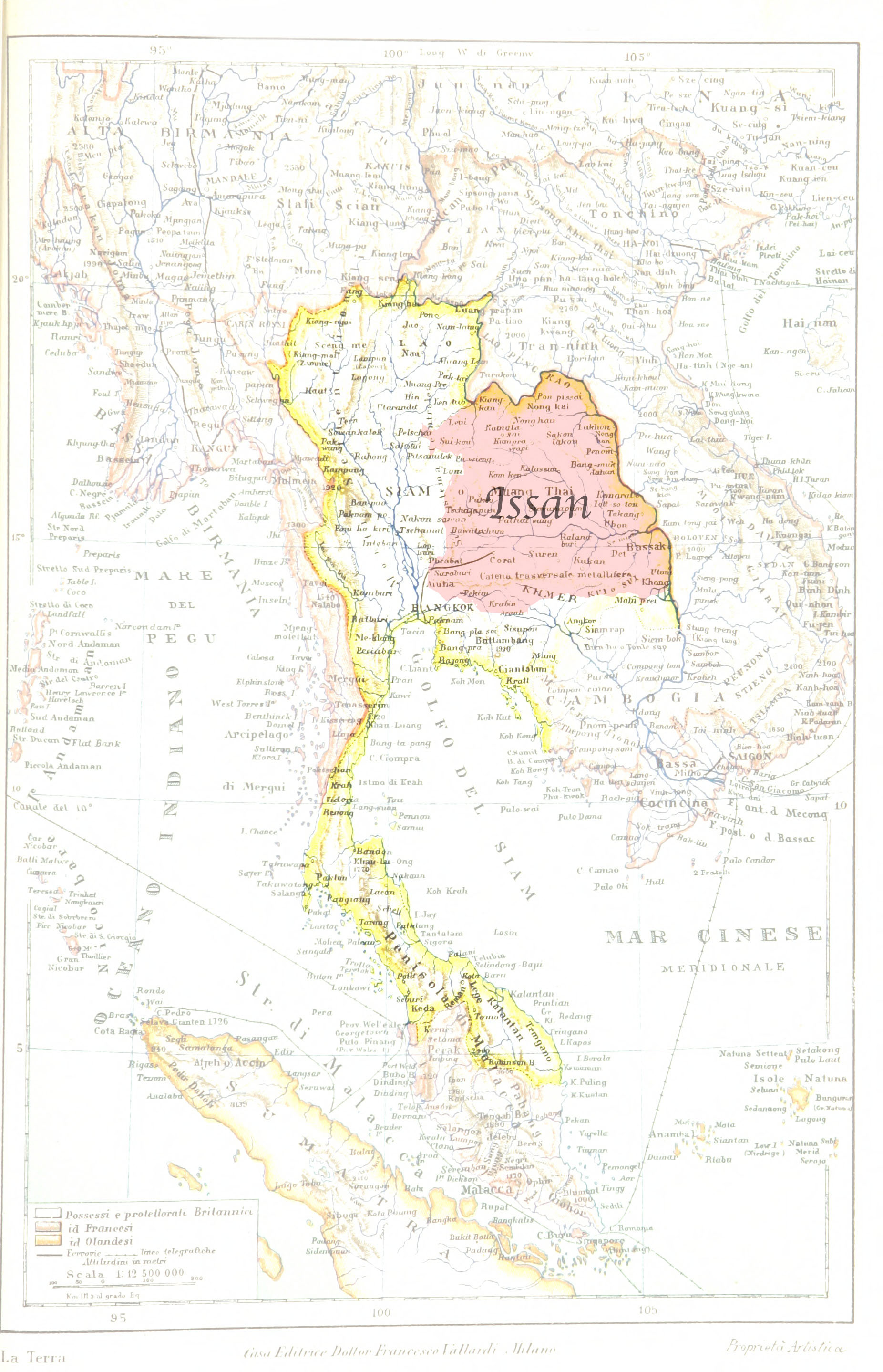

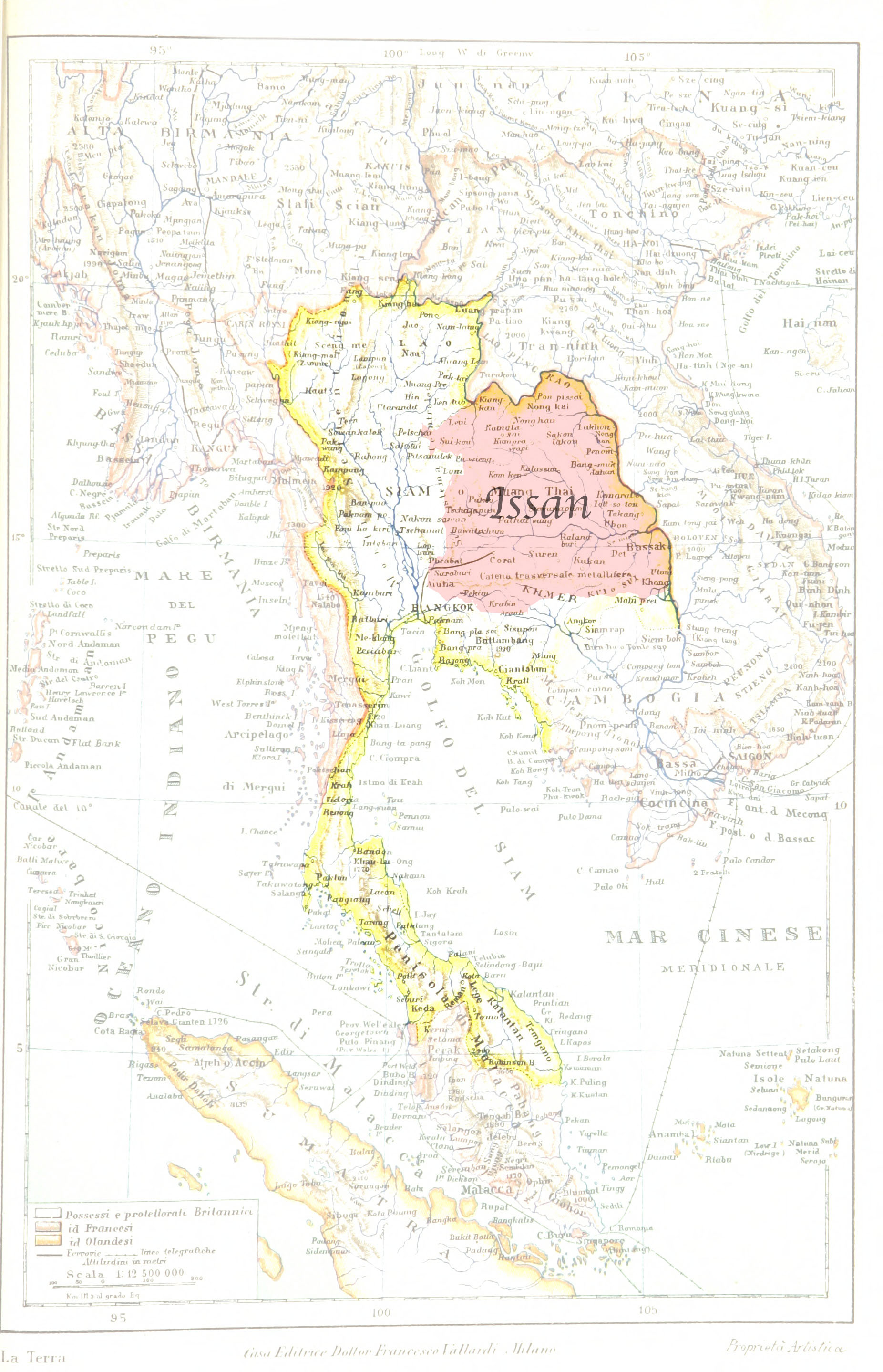

He and his partner Pei Shan Wei were astonished their restaurant was awarded three stars in June of 2022 by New York Times food critic Pete Wells—an honor not yet given to any other Thai restaurant in the city. Zaab Zaab, located in Elmhurst, Queens, barely fits six tables inside, but diners are transported to Isaan through its cuisine. The accomplishment is especially personal for Bryan who spent most of his restaurant career showcasing true, undiluted Thai flavors.

Bryan’s acclimation to the industry started young as he watched his father work as a sous chef at one restaurant during the day and at another by night. As a busboy in one of those restaurants, Bryan made good money, but lacked the passion to continue working there. He left to attend college and get an office job, but quickly realized this lifestyle was unsatisfying. He eventually returned to food when his father opened a classy Italian spot by Hells Kitchen. In the 90s, western cuisines like Italian or French appealed to customers because they were easily recognizable. The restaurant’s open kitchen layout which was meant to entice diners, ended up doing the opposite.

“Nobody wants to see a Thai chef cooking in an Italian kitchen,” Bryan said. Instead, he wanted his father’s approval to turn the space into a Thai restaurant. His father had reservations because authentic Thai ingredients were difficult to source at that time—using them hiked up prices, but foregoing them compromised the integrity of the dish. The restaurant wasn’t as successful as Bryan had hoped, unfortunately, so he moved out of New York to gain entrepreneurial experience. He spent a decade-long stint in Colorado, manning several restaurants, including a two-story spot with reservations upward of 400 per night. He moved back to New York City after 9/11 because he felt the community needed him more here.

Bryan spent some time waiting tables at restaurants like Jean Georges—his idea of a break—before opening up Blue Orchid in the quiet neighborhood of Sunnyside. Bryan relied on his industry experience to decorate his restaurant lavishly. It stood out in the neighborhood, but not in a good way he learned; the sumptuous chandeliers and pricey menu proved too unapproachable for the community. “It was too fancy!” Bryan lamented. He observed numerous food magazines expressing the absence of Vietnamese cuisine, and, after a year of slow business, conceded to rebrand and replace the menu.

After assessing what was missing in the neighborhood, Bryan pinpointed a deficiency in luxurious coffee. By chance, he met Pei at this time, who used to be a sales person for espresso machines. Initially, Pei’s boss was uncertain about the sale; he questioned, “What’s a Vietnamese restaurant going to do with such an expensive coffee machine?” Yet, Pei fully believed in Bryan and agreed to sell him a machine which he took three months to pay off. Bryan’s foresight enabled his business to take off.

The face of the block changed drastically—a couple of bars opened up and even a sex shop, which Bryan was opposed to as he felt it ruined the family-friendly atmosphere. Approximately two years later, much more than just the atmosphere had changed—a five-alarm fire wiped out Bryan’s restaurant along with others, including one establishment that had been destroyed after standing for two decades. It nearly finished him as a restaurateur; Bryan recalled having no choice, but to start over, despite being at zero. At least this time he had Pei with him. She helped him through this tragic period and thus became more involved in the business.

It took over a year for the insurance to come in which Bryan used to open Zen Yai in Williamsburg. His first obstacle was when Con Edison withheld gas the first eight months, thus delaying the restaurant opening, despite still having to pay rent. Rather than sit idly, he focused his time polishing the interior. He filled the restaurant with plants and commissioned an artist to paint greenery across the walls to give it a Zen vibe. Once the restaurant finally opened, Bryan and Pei learned that relocating would have its own setbacks. Here in trendy Williamsburg, customers did not find low prices appealing—the next-door Chinese takeout spot already offered familiar, cheap options, and there wasn’t enough temptation to switch over.

“...with accolades piling up—a Michelin Bib Gourmand; Eater’s Best Restaurant of the Year 2022; New York Times’ top 50 restaurants—it became obvious which category Bryan belonged to. "

It was time to rebrand—again—this time, renamed as Tiger Prawn with a revamped Vietnamese-Cajun menu. It was still in the realm of what Bryan was accustomed to cooking, but the concept was fresh enough to attract new customers. He brought back the artist, who sculpted the iconic eight feet tiger prawn which passerby can see hanging from the ceiling when peering inside the restaurant. The menu saw specialities like crawfish and prices were adjusted accordingly. Bryan’s ability to pivot kept the restaurant from sinking, and this quality helped him the most when he had to shut down during the pandemic.

Bryan was lucky enough to have another establishment, Eat Gai, still running in the Essex market. Deemed essential since it was a part of a grocery complex, it remained open and brought in just enough revenue. The restaurant, reminiscent of the ones back in Thailand that feature only one item, exclusively sold Hainanese chicken, an Asian comfort food. The one-item menu kept overhead costs low, while being novel enough to generate a consistent flow of diners. A chef has to be brilliantly confident or absolutely unhinged to execute this; with accolades piling up—a Michelin Bib Gourmand; Eater’s Best Restaurant of the Year 2022; New York Times’ top 50 restaurants—it became obvious which category Bryan belonged to.

Still, it was not enough to combat the burden COVID propagated. Bryan and Pei’s livelihood depended on the community, who equally required their support in return. Pei reached out to contacts who referred her to Rethink, a nonprofit that delivers meals to those in need. Although Bryan’s restaurant employees had dwindled to only a handful, they worked assiduously to give out the 3,000 meals needed, per day. Pei’s generic Chinese sounding name also picked up interest from Heart of Dinner, a charity that supplies food to Asian-American elderly. The duo realized they were one of the few Asian businesses still open and this impelled them to try even harder for their community.

As they searched further, their efforts were recognized when they received a contract from Off Their Plate, an organization that provides meals to frontline workers. Bryan and Pei were now responsible for distributing 20,000 meals, per day, throughout the city. The restaurant had transformed into a factory, with tables rearranged as an assembly line for food prep. Uniform layers were found everywhere—from stacks of packaged food, to rows of freezers, to the lines of delivery trucks down the block. The colossal task included hiring more restaurant employees, drivers and delivery people, and a second set of drivers who would tail the first set to ensure meals were properly delivered because meals that failed to reach their final destination went unpaid.

It took over a year for the insurance to come in which Bryan used to open Zen Yai in Williamsburg. His first obstacle was when Con Edison withheld gas the first eight months, thus delaying the restaurant opening, despite still having to pay rent. Rather than sit idly, he focused his time polishing the interior. He filled the restaurant with plants and commissioned an artist to paint greenery across the walls to give it a Zen vibe. Once the restaurant finally opened, Bryan and Pei learned that relocating would have its own setbacks. Here in trendy Williamsburg, customers did not find low prices appealing—the next-door Chinese takeout spot already offered familiar, cheap options, and there wasn’t enough temptation to switch over.

It was time to rebrand—again—this time, renamed as Tiger Prawn with a revamped Vietnamese-Cajun menu. It was still in the realm of what Bryan was accustomed to cooking, but the concept was fresh enough to attract new customers. He brought back the artist, who sculpted the iconic eight feet tiger prawn which passerby can see hanging from the ceiling when peering inside the restaurant. The menu saw specialities like crawfish and prices were adjusted accordingly. Bryan’s ability to pivot kept the restaurant from sinking, and this quality helped him the most when he had to shut down during the pandemic.

Bryan was lucky enough to have another establishment, Eat Gai, still running in the Essex market. Deemed essential since it was a part of a grocery complex, it remained open and brought in just enough revenue. The restaurant, reminiscent of the ones back in Thailand that feature only one item, exclusively sold Hainanese chicken, an Asian comfort food. The one-item menu kept overhead costs low, while being novel enough to generate a consistent flow of diners. A chef has to be brilliantly confident or absolutely unhinged to execute this; with accolades piling up—a Michelin Bib Gourmand; Eater’s Best Restaurant of the Year 2022; New York Times’ top 50 restaurants—it became obvious which category Bryan belonged to.

Having multiple sources of revenue was crucial and as lockdown lifted, so did the need for charity meals, thus pushing Bryan to scope out new areas for another restaurant. While driving down Elmhurst, he spotted a small “for rent” sign and immediately made up his mind—this spot would be his. He laughed as he remembered the sneakiness involved; the landlord, mistaking Bryan for another buyer, let him in and Bryan locked the door behind him, preventing others from interrupting them. After quickly inspecting the space, they came to a deal after a few minutes of negotiating. Bryan understood the spot would be highly sought after; his suspicions were confirmed when he exited the building and saw a number of interested buyers who had no idea they had just missed out.

The famous Zaab Zaab was born, but it was a sleeper at first. The course of the restaurant was completely altered when one of Tiger Prawn’s part-time chefs made an unforgettable staff meal. He recreated a dish from his hometown Isaan called chicken larb, which was so flavorful that he was promoted to head chef and sent to Zaab Zaab, right when the original chef left suddenly due to health reasons. The new chef, Aniwat Khotsopa, was initially apprehensive about his responsibilities, fearing Isaan cuisine would be too unfamiliar for American pallets. Thai restaurants in New York City typically serve street food originating from Bangkok such as the sweet and savory Pad Thai. Isaan food, which has been influenced by nearby Laos, is considered spicier and more pungent, often seasoned with fresh herbs and fermented fish. Bryan’s effort to procure quality, authentic ingredients like sadao and phe kaa paid off by catching the eye of distinguished individuals.

When Pei first noticed Joe Distefano, a talented writer and consultant, she promptly pursued his help to do PR work for the restaurant. “We are immigrants, we don’t know how to write articles that adequately express our food,” Pei confessed. Joe’s interest in the restaurant and subsequent PR campaign garnered the attention of numerous online publications alongside Pete Wells. The duo, who didn’t expect anything higher than one star, could not believe they received three stars from him. They first read the glowing review standing at the newspaper stand that morning and then proceeded to buy up all the newspapers. The restaurant grew so successful that Bryan reopened his Williamsburg restaurant as Zaab Zaab’s second location. With Bryan’s forward thinking and Pei’s charm, and a bit of luck, the restaurant’s newfound reputation propelled the two to open a couple more locations.

With successful eateries in some of the trendiest neighborhoods, Pei set her eyes on conquering up-and-coming neighborhood Flushing, which largely houses Taiwanese and Chinese populations. Pei, who is ethnically Taiwanese, saw this as an opportunity to feature diverse Thai dishes to a community close to her heart. While awaiting to open up shop in the newly constructed Tangram Mall, Zaab Zaab was selected as one of the 17 stalls to open at Market 57 in Chelsea. The James Beard-backed food hall chose vendors based on those who have participated in programs or events with them previously. Thus, they fast tracked another location of Zaab Zaab at the food hall while opening their latest restaurant.

The food served in his restaurants are curated for Thai palates and that’s why it works, Bryan said. The expensive, fresh herbs, culminate in potent flavors that other restaurants fail to replicate because they dilute the spicy-salty-sour balance with too much sugar. The tiger prawn he serves, each the size of a forearm, fills the restaurant with the punchy aroma of fish sauce and Kaffir lime. The addition of duck larb (Zaab Zaab’s most acclaimed dish); steamed branzino topped with garlic and cilantro; and even lemongrass soup filled with offal, triggers salivation on sight. Though Bryan has a winning menu, he’s acutely aware of the constant grind to stay relevant in today’s digital age, especially given the current economic downturn. He wants to show people that Thai food isn’t just simple street food, but can be fancy too.

Since his teenaged years, Bryan has watched the Thai community expand from two mom and pop restaurants to thousands more in New York City. Today he, too, has made a significant mark in the community. Although disaster struck twice—with the first restaurant that burnt down, followed by the pandemic a few years later—he and Pei persevered because of their ability to consistently adapt. Despite the success of their restaurants, the two are incredibly humble about viewing themselves as a small part of their community. They continue to work alongside several nonprofits to serve delicious Thai food to both the Asian community and the underserved.

Since the writing of this article Bryan and his partner Pei have also been nominated for a James Beard Outstanding Restaurateur award.

The original location of Zaab Zaab. It's a cozy restaurant with 5 tables. Woodside ave in Elmhurst, Queens.

The Neon Brunch King of Astoria Queens:

Donnie D’Alessio, Comfortland, and the Circle of Inspiration

Read More...

Convivium Osteria

Rustic Italian food in the heart of Park Slope.

Read More...

NYC Street Food

One of NYC's most iconic institutions.

Read More...